Fulfilling the dream

The Kennedy family is the closest thing we’ve had to an aristocracy since the 18th century Order of Cincinnatus, made up of Revolutionary War generals who were suspected, at the time, of trying to institute an American monarchy. The Kennedy history of self-fashioning, on the other hand, is about as “American” as an aristocracy could be: after arriving in America as poor and outcast as most of their fellow Irish emigrants, they rose the ranks of Boston politics through their local businesses, and plenty of hand-shaking.

Generations of Kennedys ruled Massachusetts. Patrick Joseph “P.J. ” Kennedy, JFK’s paternal grandfather, bought saloons and other businesses in Boston before his election to the commonwealth’s House of Representatives. John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, the future president’s maternal grandfather (also the son of immigrants) saw most of his siblings and his mother die of preventable diseases before getting involved in politics and eventually becoming mayor of Boston. From there, the family grew more powerful, all the while swimming against an active current of anti-Irish Catholic sentiment perpetuated by Mayflower-descended Boston Brahmins. President Kennedy’s parents, Rose and Joseph Patrick “Joe” actively placed themselves in the middle of this elitist rejection, paving the way for the next generation’s eventual acceptance. Rose and Joe became the talk of the town, and their children—Jack, and his older brother Joe, especially—would eventually follow suit.

It’s the quintessential American success story, the fulfillment of one of Steinbeck’s best (though perhaps misquoted) lines: “the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires. ” The Kennedy family arrived to America as temporarily embarrassed millionaires, an error that they corrected quickly. They fulfilled what so many hoped would be their own destiny in the land paved with gold.

Of course, they were an exception to the reality of America: John F. Kennedy was born at the tail end of the Progressive Era, a generation of social and political action, marked by Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890) and the Statue of Liberty gaining its signature lines, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses, ” in 1903, among an entire sub-economy of social criticism. It was another chapter in that great and complicated American narrative: the story of hating the rich and their institutions, yet wanting desperately to join them.

Jack seemed fixed on a page conveniently placed between successive chapters of that book: World War I and its extravagant post-war period lessened the importance of class in America, and he was insulated in successive private schools all through the Great Depression. By the time college and military service had passed, Jack entered public life at one of the greatest times in American history to be wealthy: all of America had helped destroy Hitler—including rich factory owners working with the government to supply the front line, and investors standing behind the war effort— and we celebrated as a nation indivisible. Daniel Bell pronounced it the “End of Ideology” in his book by the same name: the extreme right and left converged to form a stable centrism upon which American politics operated for the next four decades. More than anything, in the post-war boom, the American Dream was alive and well.

Kennedy’s life and career were firmly set in the self-assured “post-war” era. The story of John F. Kennedy’s political fortune goes beyond the conditions of the time, though. It is very much one of institutional power, and of rigorous planning on the part of his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr.

The Rising Son

If evidenced in nothing else, John Kennedy’s application to Harvard—remarkably scant, almost certainly because he was guaranteed admission no matter what he wrote—betrays some sense of the entitlement that the Kennedy children must have felt in their youth, perhaps rightly so: their father, after all, was one of the most influential men in America. His children were some of the most educated, the wealthiest, the best connected, and the most promising. Why shouldn’t they have it all?

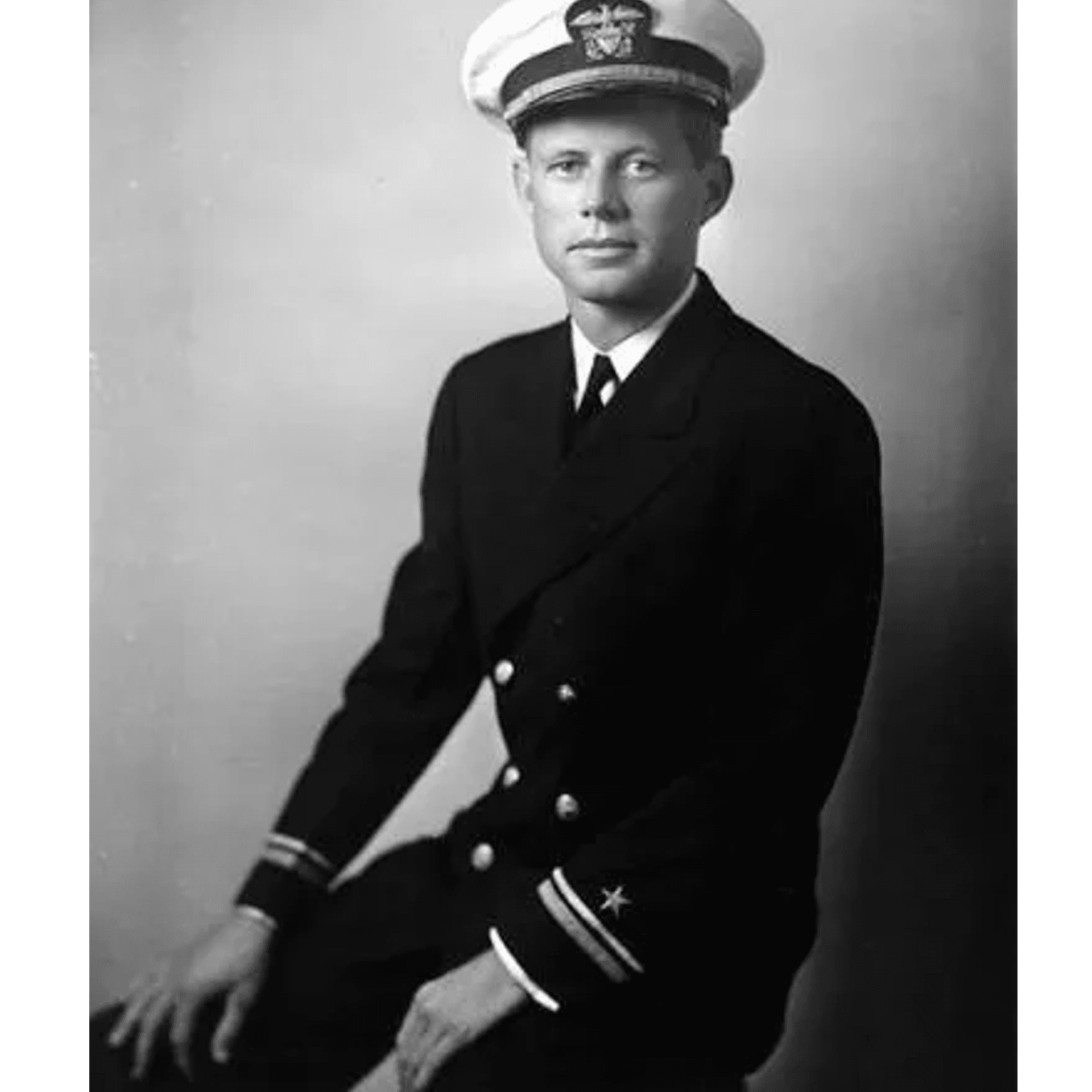

It was this massive system of privilege that saw John Kennedy through his college years, and the one that, despite his physical weakness due to Addison’s disease, landed him an enlistment in the Navy.

And it was this system that, after not noticing a Japanese destroyer making a cargo trip until the ship had split Lieutenant Kennedy’s PT 109 in half, made him a war hero: after he and his men swam ashore a nearby island, Kennedy’s quick thinking and bravery (or so the story was told) saved the crew from almost certain death, either by starvation or detection by nearby Japanese camps. Gallant though it was, the publicity effort that followed was even more impressive. News of Kennedy’s military valor spread across the country: the Harvard grad, son of the former ambassador to America’s greatest ally, author of the best�selling book Why England Slept, war hero.

He was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medals, and, less than two years later, won his first election to Congress. His father had convinced the current office-holder, Congressman James M. Curley, to run for Mayor of Boston instead of seeking re�election.

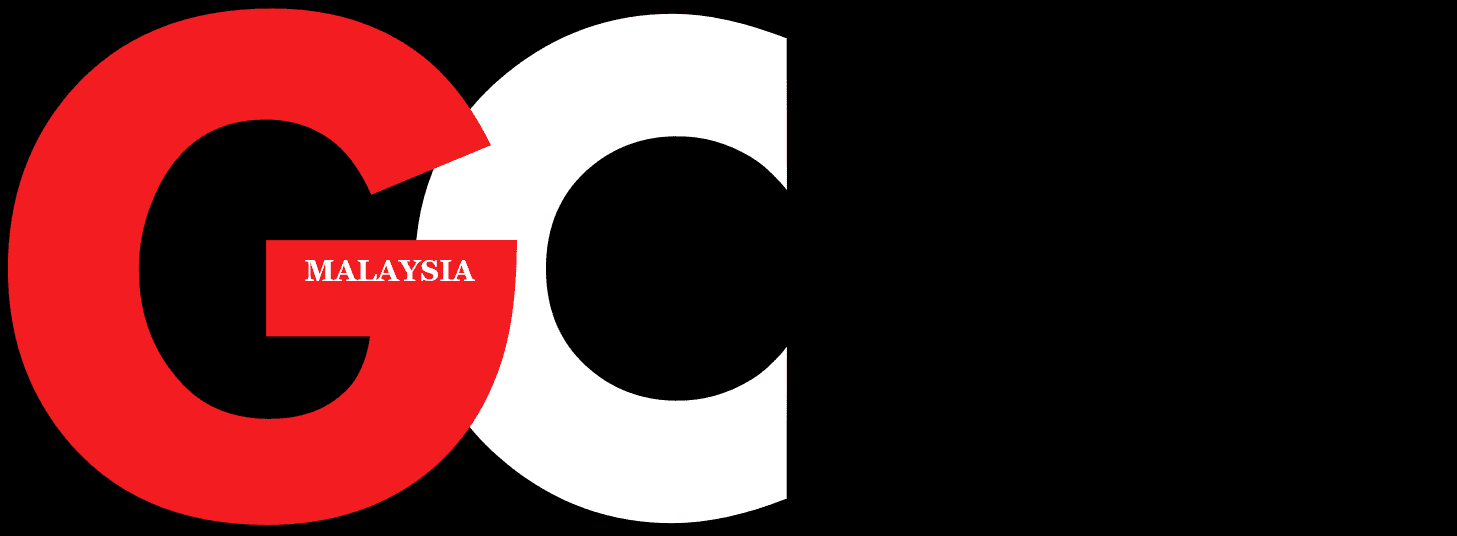

And then John met his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier, from a family of equivalent prestige in New York. The new couple’s ritualistic Catholicism and roots in the American elite, argued Peter Collier and David Horrowitz’s The Kennedys: An American Drama, gave them a special understanding of “spectacle, ” and especially of the sort that looked great on camera. John and Jacqueline’s wedding had been grandiose, attended by all of Washington’s socialites. The Kennedys were knights in shining armor: guards from the American upper class that bestowed upon the country their youthful energy. They were success, in every form.

Jack’s presidency continued in the same strain. The first lady brought America into the White House in new ways, leading camera crews around in virtual tours and opening “The People’s House” in unprecedented ways. Jack, for his part, was minutely attuned to pop culture, and ran an administration known for using audiovisual media, instead of simply responding to it. He was the first president to hold live, unscripted press conferences, which gave America the chance to see his wit and humor in real time. The era we’ve chosen to evoke with “Mad Men, ” might not have been far off, after all: the DNC paid advertising firm Guild, Bascom, and Bonfigli $2.41 million in 1960 to make Jack Kennedy a political force, with ads featuring lines of African Americans waiting to vote, West Virginian Coal miners with blackened faces, and groups of smiling suburban women, all singing in unison, “Kennedy: A change that’s overdue!” It is this culture—of youth, energy, enthusiasm, “benevolence”—that contributes as much to the legacy of Kennedy’s presidency as his handling of the Berlin Crisis or the Cuban Missile Crisis.